Japan's Quiet Realignment: What LDP Voter Outflows Tell Us About 2025

Findings from the Japan Values Today (JVT) Survey, 2025

Summary

Japan’s electorate is not polarizing so much as re-sorting around pragmatism. The ruling LDP’s “core” is shrinking and hardening into a status-quo bloc, while a wider periphery now rewards functional change over ideology. That is why Sanseito—less a classic right-wing vehicle than an inward-looking, anti-establishment protest with everyday concerns—has become a surprising magnet for defectors. If the LDP answers only its most defensive core, it risks losing both moderates and swing voters.

The Big Shift: Reform Expectations Are Rising—and Hardening

Two simple statements capture the mood in 2025:

- “Reforms are necessary even if they result in short-term destabilization.” 55% agree.

- “Japan needs strong leaders to break up vested interests.” 59% agree.

Both are up roughly five points since JVT 2022. But the movement is uneven. Among voters who rate the LDP very highly, net agreement with reform has collapsed (49% agree / 41% disagree; down about 30 points from 2022). The core has “purified” into a smaller, more defensive, status-quo constituency—understandable after a string of setbacks in 2024–25 and a lack of wedge-issue mobilization in the 2025 House of Councillors race (LDP won 39 of 125 seats).

By contrast, among those who somewhat rate the LDP, reform expectations edged up (62.9% agree / 21.8% disagree). Neutrals also moved toward reform. In other words, soft supporters and fence-sitters want change that delivers near-term, tangible payoffs. Among the anti-LDP, the hardest critics became more reformist (net +49, up roughly nine points since 2022), whereas the “somewhat low” raters backed off. The hesitant are skewing young.

Takeaway: The electorate’s appetite is not for abstract “change,” but for operational fixes—the kind you can feel in six months.

Defection Dynamics: Performance Over Ideology

When we track movement from the 2021 LDP vote to 2025 party choices:

- LDP → other party movers: 79% agree with reform / 14% disagree → net +66.

- LDP stayers: 48% / 28% → net +20.

The gap, +45 points, widened from 2024 to 2025.

Defectors decide with less hesitation; stayers are ambivalent and disruption-averse. And crucially, many defectors are not leaving the LDP over ideology but over functional performance, inflation fatigue, administrative efficacy, overtourism management, everyday frictions.

This is why Sanseito has become the principal absorber of outflows. It wraps anti-vested-interest rhetoric in a promise of livelihood utility—not a grand theory of the state. The Japan Conservative Party (which gained fewer seats) draws a more ideologically intense profile—important, but with a smaller gravitational pull on the LDP’s traditional periphery.

Under a dominant conservative leader (think Abe-era), the conservative ecosystem tended to align with the LDP. Under a weaker right-leaning standard-bearer, there is no automatic rally-’round effect.

Who Are Sanseito Voters, Really?

Stereotypes mislead here. On the surface, Sanseito appears “hard” because it marries change talk with quantitative limits on foreign workers/tourists and cooler views on free trade. Yet the constituency is best described as inward-looking, isolationist in tone, and motivated by discomfort with “excessive liberalism” rather than by a coherent right-wing ideology.

Economically, Sanseito supporters are expansionary but not redistribution-driven. They are not concentrated in the very lowest income bands (unlike Reiwa or the JCP); across incomes up to ¥7 million they sit in a fairly even 11–14% range. About 60% endorse “self-help,” well below the LDP and Ishin but higher than DPFP. Think less “ideological right,” more pragmatic localism with a defensive edge.

Culturally, they can sound traditional. On gender roles, Sanseito’s “women are suited to housework” share (23%) sits slightly below the overall average (24%), and far below Japan Conservative Party and the LDP. The share is even lower than JCP and Reiwa, although they both are defined as a progressive, leftist party.

Bottom line: At least two-thirds of Sanseito voters are ordinary people. Only about 3% of all respondents for JVT 2025 survey are intensely committed to so-called Sanseito’s ideology. If the LDP chases that vocal fringe, it will hemorrhage both core moderates and soft supporters—and gain little in return.

The “Third Force” Isn’t New—But Its Content Is Changing

For decades, Japan’s left–right cleavage turned on security and the constitution. Support for strengthening the U.S.–Japan alliance has long been the best predictor of a LDP vote. Generational turnover—especially the rise of the second baby-boomer’s cohorts—is muting that axis. The next decisive cleavage will not be about security. On JVT’s long view (since 2019), the inflection should be clear before 2030.

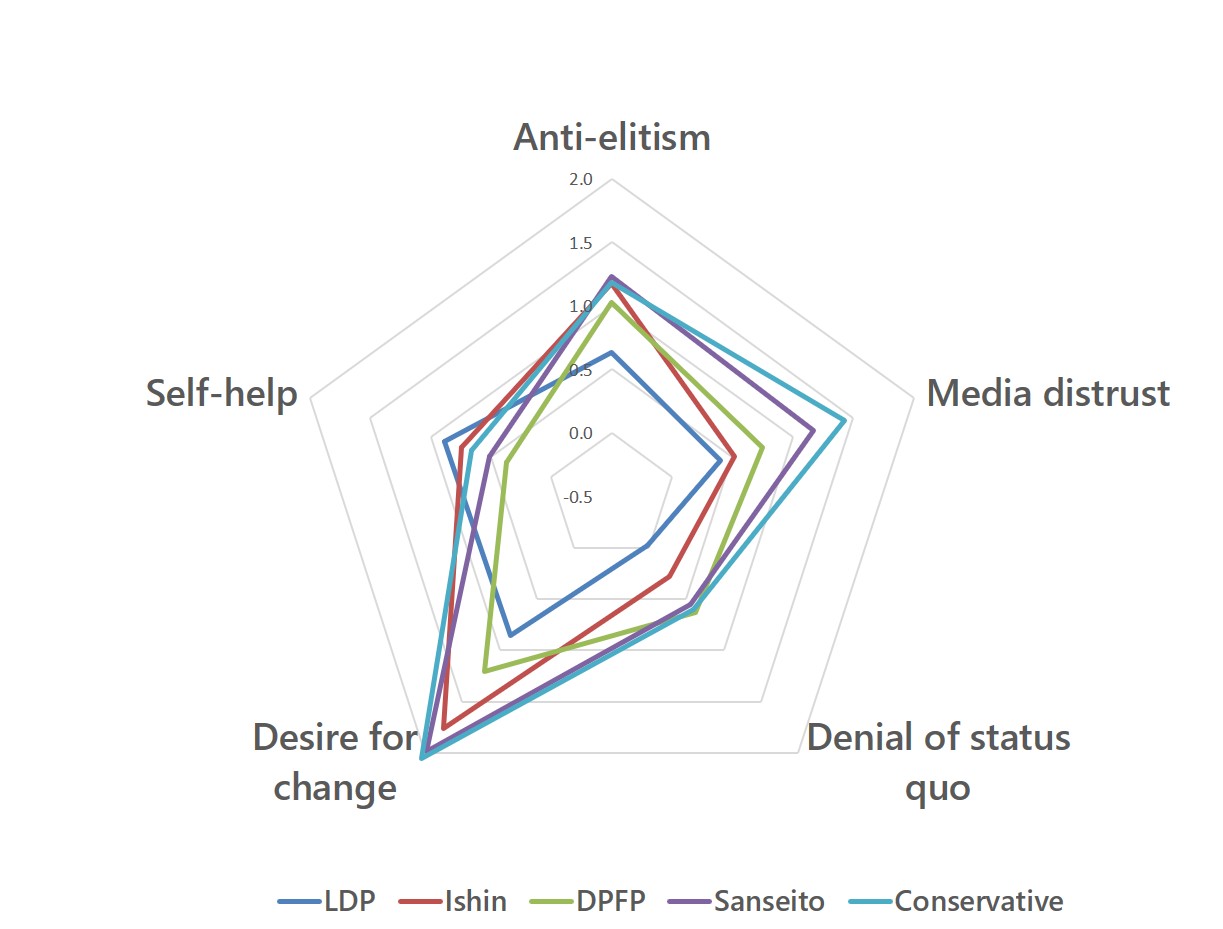

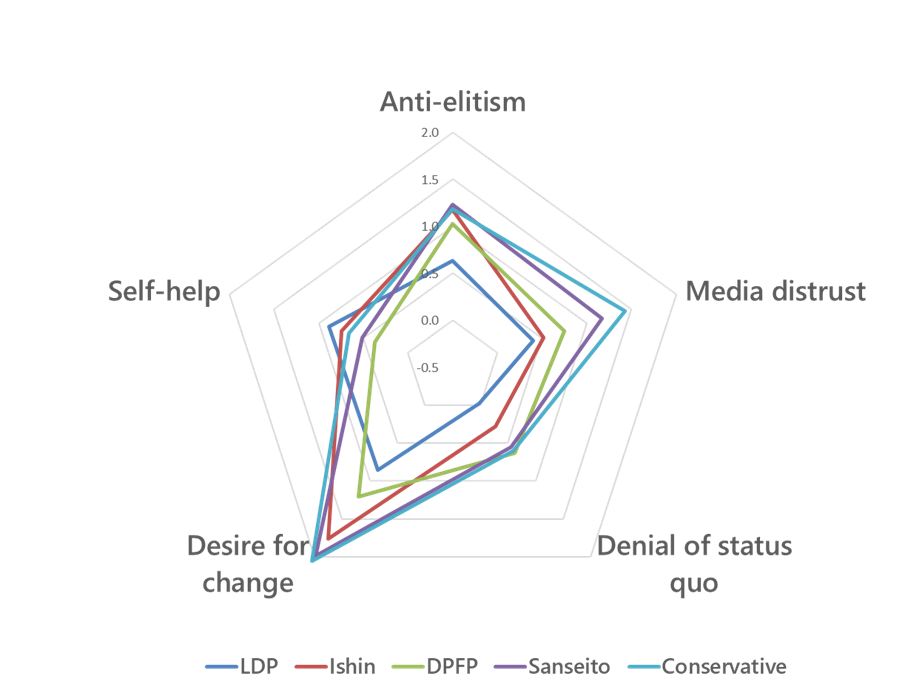

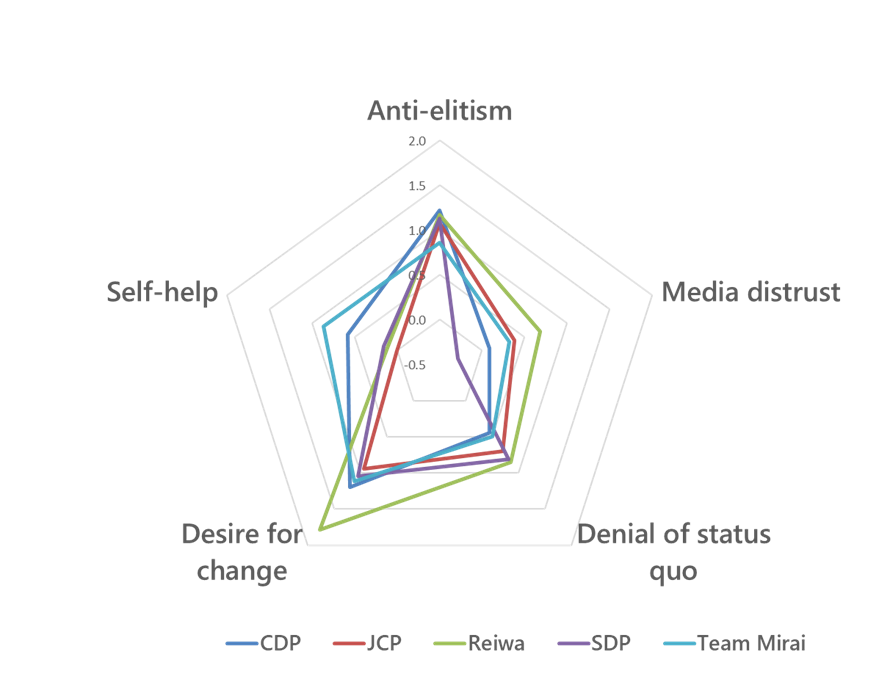

A non-security “third force” has existed in every era since the end of Cold War, with a proportional representation district potential just over 10 million votes. Its character is non-ideological: realist on security, domestic-issue-first, high reform expectations, strongly anti-elite. In below 2025 radar charts, Sanseito and the Japan Conservative Party spike on change and status-quo rejection. Ishin shows anti-elite energy too (often in anti-Tokyo tones), but governing Osaka has saddled it with status-quo affirmation—nudging low-status-quo voters outside Kansai toward Sanseito. Meanwhile, younger cohorts value “self-help” less, which helps direct security realists among the youth toward DPFP and Sanseio.

What This Means for the LDP (and Everyone Else)

The LDP’s organizational periphery is blurring. Those voters respond to non-ideological reform offers, “make the machine work,” more than to identity or grand narratives. The 2025 demand spike is a pragmatic plea for fixes “even at short-term cost,” not a culture war. Empty slogans are counterproductive; politicians must tell a cost-effectiveness story.

Also, Japan needs generational renewal—not as a slogan, but as a work plan. Fine speeches matter, but the electorate’s patience is now tied to execution. The window is open—briefly—for those who can show results, quickly and credibly.

*Methods Note

The Japan Values Today (JVT) survey is a nationwide opinion study conducted by Yamaneko Research Institute via Macromill’s online panel since 2019, with age quotas and weighting-back to population benchmarks.

Sample sizes: 2,059 (Aug 2025); 3,152 (Feb 2022); 2,060 (Aug 2019).