Japan’s 2025 Upper House Election: A Pivotal Moment of Reckoning

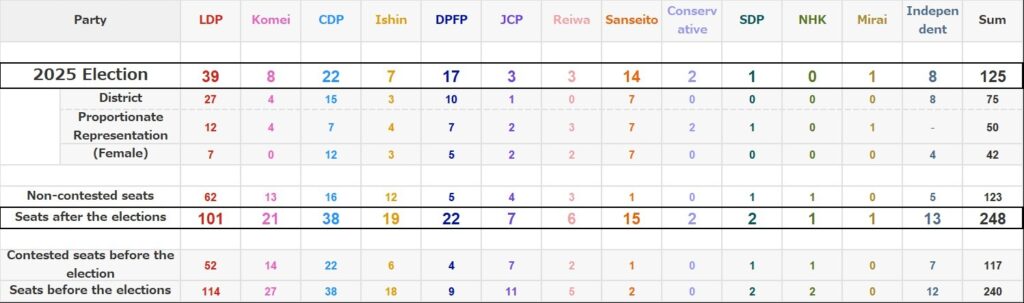

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) faced a terrible defeat in the July 2025 Upper House elections (see, chart 1 for the result). Despite the drubbing, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba vowed to stay, only to be criticized heavily from his own party members. Now, the LDP stands at a crossroads: fleeting scramble for expanding coalition or a deeper reevaluation of identity, strategy, and voter relationships. Both are essential, but the latter is paramount.

Leadership: Who Shapes the Next Chapter?

The choice of the next party president is critical---not merely for headline-making optics, but for guiding Japan’s long-term political trajectory. The contenders offer distinct trajectories: Shinjirō Koizumi, son of former PM Junichirō Koizumi, embodies youthful renewal. His elevation would signal generational turnover and a readiness for structural reform.

Takayuki Kobayashi, an emerging talent free from dynastic legacy, might appeal to voters seeking fresh voices--but without high-profile charisma.

Sanae Takaichi, right wing female politician who led the leadership votes in the initial round previously, brings both symbolic factor as the first female PM and conservative ideological clarity.

The party could also present technocratic choices--like current Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi, Finance Minister Katsunobu Kato, or Toshimitsu Motegi. But none offers the dramatic pivot voters demand. Stability without narrative change won’t suffice.

Seat-to-Seat Strategy vs. Soul-Searching

In the immediate aftermath of the defeat, tactical questions predominate; can the LDP expand coalition ties? Will opposition parties ally or abstain? These are short-cycle dynamics--worth attention, but insufficient for long-term vitality.

Instead, the LDP must reexamine, and redefine its core raison d'être. What values will rally its constituents? How will it show it truly understands and serves their needs? Reconstructing this ideological framework is imperative, but it demands boldness and introspection.

Why the Defeat? Lack of Wedge Issues

The election loss stemmed from the absence of wedge issues---divisive, emotionally charged policy battles that force choice. The LDP trudged into campaigning without championing such issues. Instead, it reactively followed opposition’s initiatives. From tax relief, immigration policy, to medical reform, etc. But it never led the agenda setting. The LDP made its argument on their competitiveness; subsidies, tariff negotiation credentials, industrial policy, and fiscal restraint opposing consumption-tax repeal…but they were not wedge issues at all. The argument lacked a values-driven narrative, a moral or ideological edge in the first place.

The LDP stumbled into the election clutching nothing but Shinjiro, the Agricultural Minister’s success in deploying rice reserves to offset shortages, without advancing any wedge issues. Amid public disillusionment, political funding scandal fatigue, and economic anxiety, this timid position proved fatal.

Some still naively hoped that branding the DPJ years (2009-2012) as a “three-year nightmare” would suffice to block a regime change. Some anti-Ishiba MPs within the LDP even believes that once in opposition, the CDP-led coalition would collapse in disarray---and voters would quickly turn back to the LDP.

But people often rewrite the history. After the DPJ’s short tenure, Abe’s long reign (almost 8 years) followed. So LDP members came to believe that it was inevitable---yet, the LDP’s return wasn’t manifest destiny at all, but rather because of the DPJ’s self-inflicted failures. To the general public, three years under DPJ government were seen as merely a repeat of the short-lived administrations and revolving-door prime ministers that had characterized the preceding LDP governments.

Abe’s Blueprint: Wedge, Repeat, Mobilize

Understanding the path to recovery requires study of the Abe era. Shinzo Abe repeatedly deployed wedge issues--most notably security legislation and constitutional revision, to polarize debate. He followed a cycle:

Define a wedge issue, spotlight it.

Enact contentious laws, harnessing political capital expended.

Call fresh elections to revalidate authority and reset legitimacy.

This rhythm generated forward momentum and cultivated genuine voter enthusiasm. Central to this was Abe’s direct appeal to LDP core values: national pride, global stature, desire for realism, constitutional reform, strengthening the alliance with the US, and strong leadership. Even controversial rhetoric served to crystallize a sense of adversarial identity; “us versus them.” Supporters didn’t merely stay, they flocked to the polls.

Democracy Demands Division

Critics argue wedge-based politics fractures society. But history shows: when governance lacks clear frames, apathy and authoritarian backsliding ensue. Democracy thrives on choice, competition, and narrative battle. Political parties must tell stories, define camps, and inspire engagement. Without this, politics dissolves into a bureaucratic inertia.

By looking at the Chinese Communist Party, you can understand this clearly. China does not have elections in the democratic sense, yet there exists intense political competition. Since every meaningful political actor must be in the CCP, that competition inevitably takes the form of exchanges of obligation and loyalty, factional ties, regional or clan affiliations, personal relationships---as well as distrust and revenge. Even in business dealings, it is customary to gather broad intelligence from a partner’s regional origin to their personal network. Because without understanding someone’s background, you cannot grasp the vital “context” in China.

Therefore, one of the fundamental purposes of a political party is agenda-setting. That’s a somewhat refined way to put it.

To express the reality in plainer terms: in a democracy, camp formation and continued mobilization are necessary costs for the very survival of democracy itself. Voters---whether knowledgeable or not---must choose something amid a vast sea of possibilities. Political forces “divide” them by offering a curated menu of values and thrusting those values into conflict, thereby generating the political heat that democracy requires. Sustained mass mobilization is essential to prevent governance from drifting toward elite domination---or, in an academic term, oligarchy.

Faction Dissolvement and Elite Detachment

The LDP dismantled its internal faction system under the guise of modernization and reform to answer heated debate over funding scandals. But in doing so, it lost structured competition. Factions previously served as incubators of new ideas, collective discipline, and ideological coherence. Their dissolution left only politicians’ individual interests and political survival.

Now, LDP MPs call for Ishiba’s resignation post-election, trying to figure out who’s next. This intensifies a disconnect between party elites and the grassroots: the latter increasingly view the former as remote---or even out-of-touch.

Is This Populism? Unpacking the New Wave

Elections saw gains by parties like Sanseitō (“Japanese First,” far-right party) and Democratic Party for the People (DPFP, more populist version of the “Labor,” so to speak), while established party like the CDP (the biggest opposition, social democrats), Communist Party (JCP), reformist party Ishin (local party in the western area) stagnated. Some label this a populist awakening in Japan---and they’re right, to an extent.

To be sure, populism is fundamentally about empowering the majority against perceived elites---not inherently negative. However, modern populists in advanced democracies often promote their claims like critiques of minority “privileges”, unrealistic promises, and concentrated power. These tendencies respond to socio-economic anxiety amid rigid systems. Yet, Japanese populism is at an embryonic stage: at least not the stage of MAGA movement. 14 new seats of Sanseitō and 17 new seats of DPFP does not match 47 new seats of the ruling bloc. A true populist surge in Japan might still lie ahead---likely within the next decade, as generational shift erodes established party alignment.

Tectonic Generational Change

The ruling and opposing mainstream parties continue to depend on older voters---Japan’s Baby Boomers and the above. But upcoming cohorts---the children of Baby Boomers, Gen X, and Millennials, present radically different profiles. Security and constitutional revision resonate with those in their 60s and older, mostly in their 70s; younger voters prioritize economic aid, everyday life, and party’s image gained through TikTok and YouTube.

Over time, wedge issues tied to national security will fade, and a more inward-leaning conservative populism could rise---potentially second in national rank.

Thus, assuming giving the administration to the moderate oppositions, watch them fail and swiftly get-back to the power strategy would be naïve and unrealistic. The middle-aged cohort still supports the LDP, relatively speaking, but even them would not prioritize security issues.

Thus, wedge issues around national defense may no longer ignite mass concern. Instead, economic-cultural combinations, connecting personal finance, national identity, and social cohesion, may become the new battleground.

Sanseitō’s Rise: A Strategic Fill-in

Sanseitō’s rise is not an accidental byproduct of global populism---it reflects a strategic adaptation to Japan’s shifting political landscape.

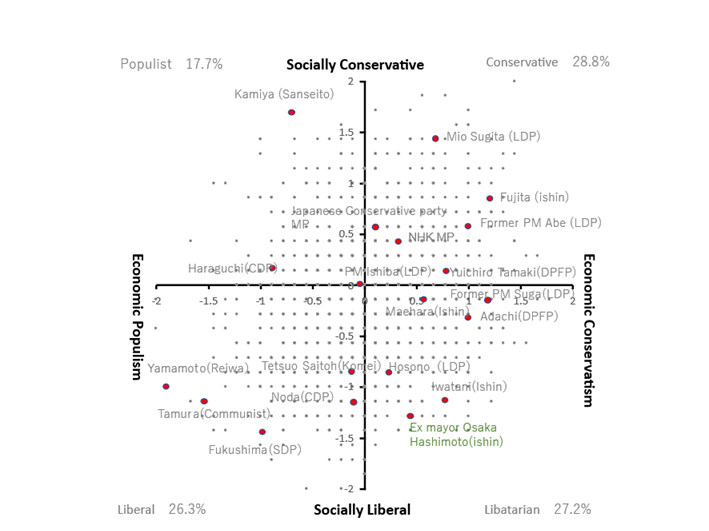

As the traditional security axis wanes, new spaces open for domestic debates. But neither the liberals nor the conservatives fully address pragmatic domestic anxieties. Sanseitō stepped into the “socially conservative/economic populism” niche---an underrepresented quadrant (see, chart 2).

There was also a prelude for it. Reiwa Shinsengumi, the progressive economic left and anti-nuclear power party established in 2019, also shifted debate by focusing on immediate economic issues like tax cuts and grants rather than constitutional or WOKE agendas. It first attracted radical left-leaning middle-aged supporters and economically distressed voters. As Reiwa pulled security debates off the center stage among the liberals, Sanseitō seized the moment---embracing expansionary fiscal policy, immigration restrictions, organic farming, and social policy positions that bridged right-leaning conservatives. They align themselves with both economic populists and cautious conservatives. Comparable to Germany’s political shifts---where the Greens peaked and declined, then AfD surged---Sanseitō reflects how ideological boundaries blur when institutions stagnate.

Ideological Charting

Positioned in the top-left quadrant (see, Chart 2)---economic liberalism and social conservatism---Sanseitō occupies a unique niche in Japan’s political map. This niche had long remained underrepresented. Sanseitō capitalized on it expertly.

Some research suggest that a part of LDP conservative supporters drifted to Sanseitō seeking preservation of social norms.

In fact, some famous right-wingers in LDP lost their seats in the elections. Now, it is easier for the right wingers to be elected from Sanseito, rather than from the LDP.

Challenges for the Liberal

The surge of Sanseitōs also raises questions: it suggests mainstream insistence on principle-based liberalism may be politically insufficient---and that parties must forge strategic alliances with voters concerned about cultural cohesion, economic fate, and national identity.

Victories for the right hinge not on a constitutional or identity overhaul, but on forging micro‑alliances where economic and cultural anxiety intersect.

The Collapse of Abe-ism

Above all, the existence of former PM Abe acted as a bulwark---reconciling globalism with tradition, economic openness with national pride. His tragic death removed that restraining influence. Now, some conservatives embrace isolationist tendencies. They embrace Abe publicly, while rejecting key parts of his policy. However, they don’t even have guts to break away from the alliance, nor do they want to pledge enormous military spending. Right-wing populism in Japan remains still “embracing defeat,” inward-focused attitude triggered less by grand nationalist ambition and more by cultural enclosure. Nevertheless, retreat from global engagement would drift Japanese democracy and economy away from progress.

What Must Be Done

Japan stands at a strategic inflection point. The fading of old conflict lines such as security, the US alliance, constitutional revision, has dissolved recent wedge issues. In their place, parties must craft new narratives: growth, inequality, local economies, national identity, and cultural adaptation. These issues demand emotional resonance.

For the LDP, the road back lies through: reestablishing grassroots bonds, including young, and newly conservative voter, revitalizing party structures (bringing back organized competition and policy think-tanks within), and crafting a coherent core values-based strategy balancing economic ambition with social resilience, international cooperation with national strength.

Without confronting elite detachment and reshaping its ideological heart, the LDP risks irrelevance. Left unchallenged, its collective drift could open ground for populist insurgents---but the alternative is to spark a politics of vision, competition, and shared national purpose.