The origins of the conservative movement

The Strong, Weak, and Vulnerable (2) The origins of the conservative movement

In the previous entry, I mentioned that the recent conservative movement embodied in Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Yasukuni is better understood as an assertion directed toward its domestic opponents. To the surprise of many international Japan watchers, Japan’s conservatives have long been marginalized and even persecuted for their views in post WW2 Japanese society. What seems to be a growing conservative movement at its core is a sense of “payback”, making up for the period of being an “ideological minority”. In this article, I will present, in more depth, the historical developments that led the conservatives to recognize themselves as the weak. I do so in hope of orienting today’s debate toward a more constructive direction, warning today’s strengthened conservative movement against the “mistakes that must not be repeated”.

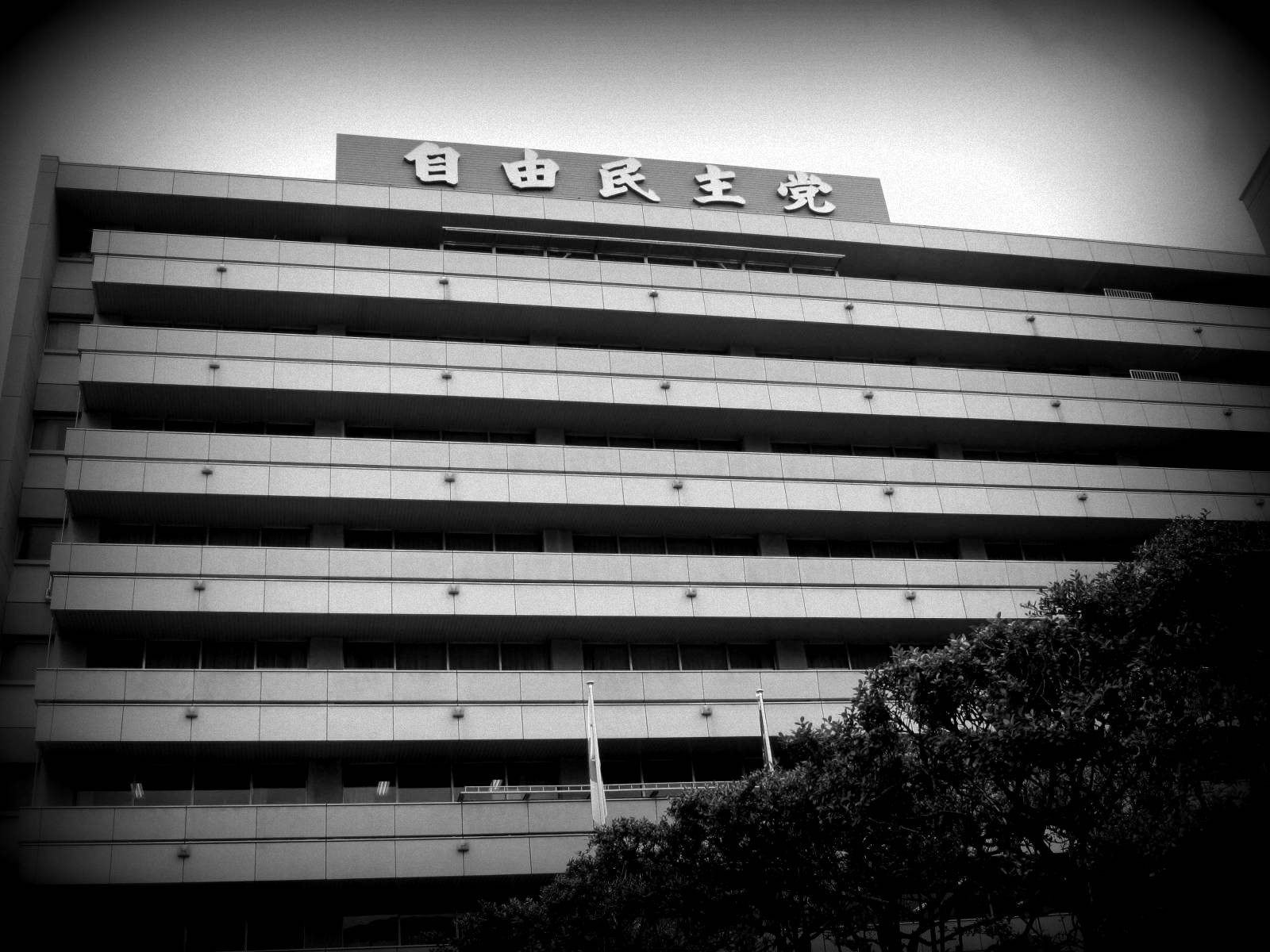

The origin of the conservative group that places particular importance on the visit to Yasukuni dates back to 1955 when the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was formed. The driving force behind the forming of the LDP was fear against socialism and communism. The conservative fractions of the LDP were clearly skeptical toward the direction of the then Prime Minister, Shigeru Yoshida, who steered Japan towards a lightly-armed nation that prioritized economic construction over military buildup. The direction to place economic development as the top priority became clearer in the policies set forth by the subsequent administrations after Nobusuke Kishi stepped down from premiership in exchange to revise the security treaty with the US. Since then, the conservative group remained a marginalized faction within the LDP for a long time.

Throughout the high-growth period of the Japanese economy in the 60’s and 70’s, the LDP succeeded in evolving into a catch all political party. The LDP did so by an artful distribution of the growing wealth as well as flexibly championing “leftist agendas” such as welfare and the environmental issues as their own. In addition, the leftist Socialist Party seemed to care more about ideological purity than actually replacing the LDP, and wasted political energy in internal battles. This political structure consequently enabled the LDP to set its ideological center line considerably to the left compared to most “conservative” parties in other developed democracies. The LDP’s success stands out in modern party politics considering it was enabled under free and fair elections.

The conservatives, also, were unable to set forth a consistent political agenda other than placing importance on conservative ideologies in interpreting history and social issues that reflect pre-war views of society. In the area of diplomacy and national security, they were explicitly anti-Communist China and anti-Soviet, but were split whether they were pro- or anti-US. This ambivalence seemed to be based on past grudges harbored against enemy countries before and during the war, rather than a forward looking understanding of the world.

In Japan, the movement to pursue “small government“, often advocated by the Republicans in the US or Conservatives in the UK hardly exists to this day. Conservatives also kept their attitude toward capitalism ambiguous, and focused rather on contending anything that would lead to destroying traditional values. On welfare, they held views that were closer to the Conservatives during the Victorian era, which was to define it as charity offered from the state rather than the people’s right. Groups holding such views exist in many developed countries, but share the same destiny of being treated as eccentric and outdated right-wingers. In Europe, these ultra conservatives still maintain a certain degree of influence; ironically, thanks to the anti-immigration and anti-European integration sentiments. But in Japan where neither immigration nor integration is a real issue, conservatives were pushed further away from the mainstream as marginal extremists.

The liberal mainstream media played a significant role in cornering conservatives in post war Japan. Time after time, the media would make top leaders assuming high office reveal their ideology on issues such as visits to Yasukuni or interpretations of history. This “fumie (or loyalty test)” to unveil the top leaders’ ideological inclinations were carried out thoroughly and often brutally. The systematic approach used by the liberals was in line with the “fumie” tradition of attempting to smoke out hidden Christians when it was banned in Japan during the 17th and 18th centuries. This obsession to marginalize conservatives was perhaps a necessary evil for Japan to prevent the reemergence of pre-war imperialistic thinking and to settle with its past. What was unfortunate for Japanese society was that it was carried out mainly through “exclusion” rather than “persuasion”.

As an example, let us compare the difference in how the social views toward historical issues and gender discrimination changed over the years. Japan’s post war constitution clearly stipulates that men and women must be treated equally. But in reality, women’s rights did not expand overnight, but rather through a gradual process that literally took generations to change. Seldom were political leaders driven from public office simply for their discriminatory words and deeds against women. But when it came to historical issues, post-war Japanese society reacted very sensitively. This comparison suggests quite clearly how heavily the views on historical issues were weighed in this country and handled as a topic to divide a particular segment of its people from the rest.

Interestingly, circumstances facing conservatives went through substantial change as the LDP’s dominance came into question. The LDP, which was once a “catch all” ideology political party is now transforming into a more “ordinary” party. The LDP built up and maintained its dominance by spreading its ideological wings as broadly as possible from left to right, making it virtually impossible to challenge them effectively. What actually led to the LDP, at least temporarily, to step down from power was the strong “vested-interests” structure and the vote-gathering system that gave it power.

However, breaking away from “vested interests” proved to be difficult even for the LDP’s challengers. When the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) snatched the administration in 2009 by identifying itself as an anti-LDP party that is against vested -interests, it was actually representing a different vested-interests mainly supported by the unions. As a result, once the DPJ rose to power, it hesitated to seriously tackle vested interests, and eventually imploded after repeatedly exposing lack of experience. Up and coming parties like the Japan Restoration Party (Nihon Ishin no Kai) and Your Party (Minna no Toh) appear to be slightly more united ideology-wise. Yet the ongoing discussions on the restructuring the opposition parties suggest that there will still be more twists and turns, including further breakups and mergers ahead. These developments outside the LDP are an inevitable by-product of the “catch-all” style LDP that remains a Goliath at the center of Japanese politics.

Another important aspect of modern Japanese politics is the diminishing influence of the “professional class” and their predominantly utilitarian way of thinking. A symbolic moment of the anti-utilitarian movement came in midst of the euphoria when Prime Minister Koizumi first rose to power. His candidacy as the LDP”s new leader was to eloquently put as to “blow up (the old) LDP”. The Koizumi administration succeeded in winning the power struggle against the mainstream factions in the LDP and the establishment in Kasumigaseki (the bureaucracy) by mobilizing conservative supporters and broadening the ideological wing to the right. Koizumi painted a positive picture of “enduring the pain” of reform, and succeeded in instilling his thoughts on a drastic economic reform agenda into the minds of the middle- and lower-income voters. This segment, often thought of as against painful economic reform actually proved to be Koizumi’s most loyal supporting base.

On the other hand, in foreign relations related issues, which was not a major battlefield for the Koizumi, he tactfully balanced the mobilization and energizing of the conservative base, and the compromises with the mainstream utilitarian way of thinking. Thus, apart from a few important conservative demonstrations, such as visits to Yasukuni, Koizumi’s foreign policies were largely an extension of the establishment’s utilitarian approach. This is evident from the actual policies the administration pushed forward, as well as from the preference of members selected for key councils and committees.

Shinzo Abe and his first administration started out with strong tailwinds, continuous from high approval ratings during the Koizumi era. At the core of the administration’s appeal was the fight against vested-interests and conservative ideology, identical to his predecessor. However, Shinzo Abe’s first administration ended abruptly in disgrace and in defeat. The turning point, many argue, came when Abe, decided to readmit ex-members who were expelled from the party for rebelling at the party’s campaign banner around economic reform. This decision stained the flag to fight against vested-interests Abe had held high. It was all downhill from this point on. The damage only worsened with political scandals from cabinet members and embarrassing policy screw ups such as missing pension records. All this led to a decisive defeat in the Upper House elections in 2007 and to the downfall of the administration.

Judging based on his remarks and writing, Prime Minister Abe appears to be a sincere conservative. As he says, he must be “deeply regretting” his decision not to visit Yasukuni during his first administration, which was a compromise with the utilitarian approach of the foreign policy establishment. But PM Abe is, at the same time, a realistic party politician who very well understands that the essence of party politics is compromise. In that sense, I do not classify him in the same group of politicians and activists hovering around his second administration who seem to show no genuine policy interest other than in conservative ideology. This group of conservative ideologues was tactfully kept away from the core group of the Koizumi administration. The reason why the current administration can bring in these conservative ideologues to the fore is because political calculation tells him that there is allowance among the public now. Rather than demonizing Prime Minister Abe of his ideology as many in the media have done, which is neither helpful nor entirely accurate, it is more important to look at the structure in which these policies have become possible.

The momentum of the second Abe administration is supported by the growth-oriented economic policies collectively known as “Abenomics” along with its conservative way of thinking. The growth strategy that constitutes the “third arrow” of Abenomics is essentially synonymous to “structural reform” used during the Koizumi era. The real political capital deployed towards tackling vested-interests is unknown at best. Tackling vested-interests has been the number one top agenda in Japanese politics for the last ten years. But now, as a result of the miserable failure of the DPJ, the political pressure to maintain intensity in the fight against vested interests has weakened significantly. If the Prime Minister’s true agenda is to follow through on his conservative policies in foreign relations, then there are likely three options that he could take to help maintain momentum and power for his second administration.

The first option would be to pray that the current growth-oriented policies will endure be sufficient for the economy to keep going. Japan is currently in a state where policies for monetary easing and government spending are already in top gear and there is little room to further boost these policies. Therefore, this is not a very realistic political option to pursue. The second option would be to fully accelerate the structural reform initiative, the third arrow of Abenomics, and hoist the flag of anti-vested-interests once again. The third option would be to capture more public support directly by expanding the conservative power base.

Hoisting the flag of anti-vested-interests means that the administration would adhere, once again, to the main political battlefield of the last decade. The political appeal of this second option is that it takes the most important issue away from opposition parties. Since the aim of taking this path is to re-establish the LDP as the superior people’s party, the majority of the people should either allow or be persuaded to accept the government’s policies in foreign affairs even if they are slightly leaned to the right. One of the important lessons that can be learned from the Koizumi era is that as long as the administration can maintain a certain amount of momentum, the public will respect the leadership and in some cases even be inclined to accept the logic and values displayed passionately by the administration. Considering the DNA embedded in the LDP, this should be the high road to take.

Expanding the conservative power base, in the context of the Yasukuni issue for example, would require the administration to create an environment that makes more people comfortable to accept the PM to visit to the shrine. According to a survey conducted by think tank Genron NPO in Japan and Korea, approximately half of the Japanese respondents answered affirmatively to the Prime Minister’s “official” visit to Yasukuni. When looking at the proportion of Japanese respondents who accepted the Prime Minister’s visit as a private individual, a total of 75% of Japanese respondents answered affirmatively. Yasukuni’s symbolism lies in its supporter’s desire to honor Japan’s war dead as well as to cherish the spirit of devotion to the state. Among the various disputes surrounding Yasukuni, there is more room for maneuver with issues such as its religious characteristics or the fact that A-class war criminals are enshrined there. In fact, some members of the conservative group have already in the past studied the possibility of changing the shrine’s charter from a religious entity, and separately enshrining the A-class war criminals to a different institution as potential options. If the Abe administration is interested in making more people feel easier to accept the conservative cause, there may come a time when the administration decides to change its course slightly to follow a path that can be perceived as approachable by a larger portion of the population, even if some hardline fundamentalists in the conservative group might oppose it.

However, if the LDP decided to go down that path, it would also mean that the LDP will continue its transition into an ordinary conservative party. And if LDP continues to stay on this track for a certain period of time, the liberal group will eventually become more cohesive, or a different political party advocating more convincing policies to fight against vested interests will emerge, and will most likely apply pressure of regime change to the LDP once again.

The choice is before the LDP’s leaders whether to remain a catch-all ideology party or to be more of ordinary conservative party. This choice will likely determine much of how Japanese politics develops in the coming years. It may have repercussions across Asia as well. At the heart of this choice is how the conservative movement defines itself.

The 70 or so years since the end of WW2 and the generational change during this time has changed the way many Japanese make personal connections to history. Majority of today’s electorate were born after the War, and naturally feel less redemption towards Japan’s history. Despite this fundamental shift, or perhaps because of this shift, the mainstream liberal media has continued to pressure the conservatives through the “fumie” approach. I believe this approach may have had a negative effect for the liberal cause by alienating the ideological middle ground, and weakened its moral leadership. The logic of exclusion, exercised too often, is similar to making derogatory remarks about others with whom you dislike. Many who have decided to support PM Abe have done so not necessarily because they share his views, but because they are tired of hearing derogatory remarks that are beyond their sense of decency.

It is clear to a majority of the Japanese electorate that, PM Abe holds conservative views. It’s also evident, though, that he is no radical. He is the grandson of a Prime Minister and son of a Foreign Minister, and a polished politician who knows the art of compromise. Despite the media’s attempt to paint him as an extremist, and whether you really like him or not, this much is pretty clear.

The irony is that the mainstream liberal media that portrayed itself as the weak underdog keeping power at bay, in reality, had massive influential power in post war Japan. Through this power, they pushed away conservatives as marginal extremists of society. Times have changed, and the liberals who portray themselves to be weak, may now be reflecting reality. For any minority group, the continuous use and abuse of the logic of the weak is self-destructive. The conservatives, now in power, exercise their power based on a minority complex entrenched in them during the long, dark period of oppression in post war Japan.

Those who have followed this entry so far should realize that the “mistakes that the conservatives must not repeat” are the mistakes made by liberals at the opposite end. In the aforesaid public survey, 8% of the respondents answered that they are against the Prime Minister’s visit to Yasukuni, regardless of whether it is “official” or as a private individual. What is important for leaders to think about when assuming power is whether one can truly respect the voice representing 8% of the public holding a minority view. This respect does not necessarily have to be shown in the form of following what the minority group says. But the minority group should not be alienated or punished for their opinions. That is what I want to think as the “Japanese way” of solving for the strong, weak and vulnerable in society.

The original version was posted on The Security Studies Unit (SSU) of the Policy Alternatives Research Institute (PARI) Also, the article was initially written in Japanese on Lully Miura's Blog "Yamaneko-Nikki" on January 15, 2014.