ARTICLES

2022.12.29 NEWS ARTICLES

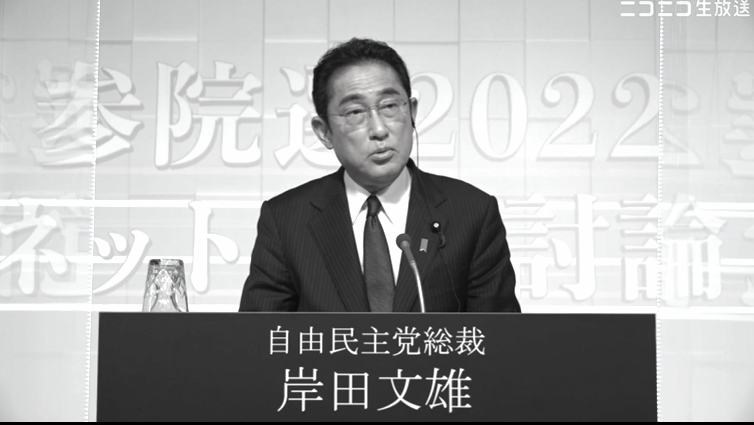

Kishida Administration

It has now been one year and three months since Prime Minister Fumio Kishida took office. Across public opinion polls, including those conducted by the media, the cabinet’s approval rating has plunged since August last year and remained low through the end of the year.

With approval ratings hovering around 30%, there are concerns about the administration's longevity. However, calls for an early resignation from Prime Minister Kishida remain limited in public opinion surveys. After all, having won two national elections in 2021 and 2022, it is difficult to imagine this administration collapsing anytime soon. The next national election is likely a long way off, and there are no indications that the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) would lose. We can expect this administration to continue well into 2023 and possibly beyond.

Approval Ratings Reflect the Public Mood

While the Kishida administration maintained high popularity for a while, the high or low approval ratings were never strongly substantiated. The approval ratings simply reflected the public’s general mood.

Undoubtedly, the administration’s initial image was favorable. Kishida’s reputation as a "clean, dove-like" figure made him appealing to many voters, including housewives who typically steer clear of the LDP for its image.

The turning point for Kishida’s image came after the shooting of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in July. Following the incident, the media intensely scrutinized the Unification Church, and Kishida’s image gradually shifted back to that of a conventional LDP politician, eroding his popularity. In other words, the support that was initially based on a favorable impression eventually dissipated for the same reason.

The Lack of a Clear Purpose

A more serious concern is that Japanese politics as a whole seems to be adrift. There appears to be a lack of a clear, purposeful direction. Why has it come to this? Simply put, it is due to the absence of political dynamism.

Politics, in essence, is a battle over a "just cause"—in Japan, this is often referred to as the “Nishiki-no-Mihata.” The definition of a “just cause” varies across eras and countries, but today’s Japanese politics seems to lack such a guiding principle, making it challenging to foster a sense of direction.

This stagnation can be attributed to a lack of power struggles that lead to meaningful change. When political upheaval is minimal, it is rare to see leaders who can champion and drive forward a compelling cause.

Reflecting on the past 30 years of "reform movements" in politics, administration, and judiciary, these changes emerged because the era and circumstances gave rise to power struggles, rather than reforms creating upheaval.

Japanese Version of “Might Makes Right”

There’s a Japanese expression similar to “might makes right,” that is “Kateba-Kangun (If you win, you would become the legitimate army).” But it implies a bit different thing, that as long as one wins, consistency in their cause is not questioned. This philosophy could be considered a Japanese specialty. Winning—or to put it in simpler terms, controlling the authority of a given “village” or sphere—is prioritized, making it difficult to frame issues in terms of justice or principle.

This attitude hinders the move toward a two-party system. The opposition becomes defined not by ideology but by its role as “the defeated.”

The only way to counteract this trend is for the opposition to promote positive change to appeal to a wide range of voters. As long as the ruling party embodies progressive change to some extent, and the opposition holds a conservative stance representing the elderly, there is little hope for a breakthrough.

So, what kind of "change" does the Kishida administration embody? To me, it appears to be merely an image of “renewal” in the sense of something new.

The Duality of the Kishida Administration

Taro Kono, who competed with Kishida in the LDP presidential election, proposed radical reforms. Sanae Takaichi highlighted her conservative stance, while Seiko Noda emphasized her feminist position.

Kishida, however, took the most conservative stance. Still, it marked the first time in a while that a member of the traditional conservative Kochikai faction took office, bringing a sense of renewed image and personnel. In essence, that defines this administration.

The Kishida administration combines an unstable element—a lack of strong leadership within the prime minister’s office—with relative stability from organizational responses as a result.

However, it would be incorrect to describe Kishida as a prime minister who only "considers" and avoids decision-making. Kishida has made three decisive moves:

- the state funeral for former Prime Minister Abe,

- alignment with NATO on sanctions against Russia, and

- imposing a ban on foreign entry just before the Omicron variant of Covid-19 spread.

The effectiveness of these decisions and the methods of implementation aside, they were undeniably swift. Even among LDP members, there is some acknowledgment (at least) that the latter two policies “hit the mark.”

The hallmark of Kishida’s top-down “decisions” is their speed. Given Kishida’s mild and seemingly indecisive personality, his quick decisions often fuel speculation. One prominent rumor is that Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso aggressively pushed for the state funeral.

Despite lacking substantiated evidence, this rumor has circulated as a semi-accepted notion in weekly magazine reports. However, any individual capable of “pressuring” the prime minister into a state funeral must be an influential LDP figure. If such a powerful figure did exist, it is puzzling why they would not have also directed necessary groundwork with the Diet.

The Lack of Leadership as a Pitfall

Returning to the topic, the mishandling of the state funeral and the protracted handling of the Unification Church issue were both the result of an unclear leadership framework, even after making decisive moves.

Currently, Japanese politics is characterized by a weak prime minister’s office and a strong party, known as the “weak office, strong party” structure. In such an environment, the administration lacks leadership, compounded by an absence of a coordinating leadership style, leading to stalled progress.

Regarding the state funeral, it was clearly a failure in the political process to secure the opposition's support. While there is no legal issue with holding a state funeral, and its significance is valid, the issue was a simple lack of groundwork.

The mishandling of crisis management by the LDP, prolonging the Unification Church issue, and the administration’s lack of proactive engagement are significant issues. However, the accumulation of discomfort without recognizing a real crisis reflects the current state of Japan.

The Need for a National Discussion on Three Major Transformations

Despite these challenges, the administration has laid the groundwork for politically challenging transformations:

Establishing "offensive capabilities" and a roadmap for doubling defense spending.

A path toward tax increases to fund these changes.

A policy direction for nuclear power plant replacement and reactor restarts.

All of these shifts have been fueled by heightened public awareness of energy and defense issues following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Kishida’s image as a dovish, liberal elite has also likely facilitated these shifts.

Strengthening security has long been effective for the LDP, as security and constitutional values are the most influential factors in LDP voting patterns.

Previously, foreign policy and security were seen as politically ineffective issues. However, the LDP’s base voters—those with a pragmatic view on security—are encouraged to vote when such values are emphasized. Thus, even on divisive issues, reforms in foreign policy and security can benefit the LDP during elections.

These transformations are significant. Nevertheless, a national debate has yet to fully unfold. The administration must make more efforts to foster understanding of their necessity.

Governance capacity and the ability to explain policy are closely linked. One reason the Suga administration, despite its perceived governance capacity, hit a wall was its low communicative capacity, which was perceived as a lack of governance.

In any case, the Kishida administration must significantly enhance its leadership, including communication and coordination. Although these are challenging tasks for any administration within its first year...